This is a re-post from Alan Caine, Co-founder of Custom College Visits. He and his wife are experts in this space and have a great deal of expertise maneuvering the college visit. You can find the original article at https://customcollegevisits.com/10-mistakes-students-and-parents-make-when-visiting-college-campuses-2/.

As a college-bound teen or parent, you have likely been dreaming of visiting colleges for a long time and are excited about getting that first-hand feel for the college atmosphere. It is a big decision, many times made with emotional gut responses – that needs to based on purpose.

The college choice is secondary, purpose is first.

If you are up against a time clock and need to get on the road, you’ll want to jump into our ten mistakes to avoid listed below. You’ll also want to do some up front strategic thinking to articulate a purpose for attending college so the final college choice is the best for your long-term goals. Here are the strategic questions that must be addressed before you take those first steps on college campuses.

- What is your purpose for attending college?

- What are your career goals?

- What are the educational requirements for the career you want to pursue?

- What employers and industries will be your primary targets once you graduate?

- What educational achievements do employers in your career path value most?

- Will you need an internship as part of your college experience?

- Which college or university should I visit?

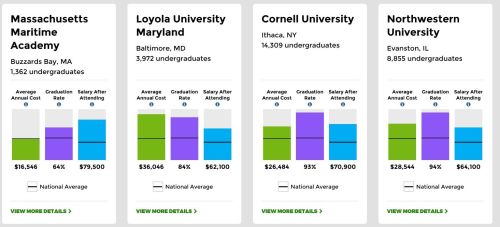

Colleges and universities will show off their best stuff (see Mistake #8). Before you invest in a visit, be sure you know some facts and figures about the university. We recommend a great resource called College Navigator as a “must use” information repository. Whether you have already made up your mind or need to narrow your list of choices, this site has extremely important information you won’t find available on campus. For example, would you want to visit a college that has a first-year retention rate of 50% or a four-year average graduation rate of 40%?

For many students and parents, the strategic questions seem so difficult that they are bypassed by the rationalization “we’ll figure it out later”. Even some education scholars have suggested high school students aren’t capable of finding valid answers to those questions until perhaps their sophomore year of college. Yet, these same academic scholars expect students to make the decision to choose a college or university.

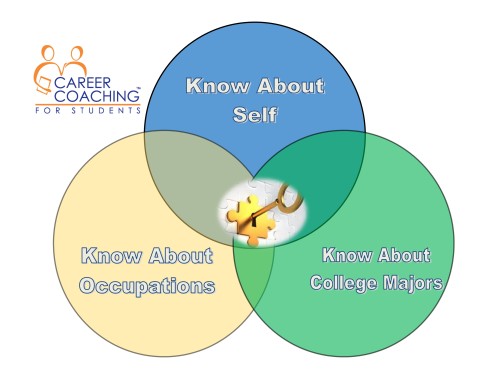

From a career planning and coaching perspective, the questions above are exactly what should be focused on in high school. The answers will evolve and student confidence in those answers becomes stronger with an intentional approach to the research process. AND, you’ll have a much more positive and fruitful college visit experience. Most if not all high schools as well as colleges and universities don’t offer effective guidance and support to answer these critical questions. The Career Coaching for Students™ program provides a proven and effective method for answering these questions in a manner that empowers the student and eliminates the fog.

Before you plan the college visit road trip…

Learn from those that came before you.

As you plan your college visits, consider the following ten mistakes many students and their parents have made. To get the most out of your college visits, avoid making the same ones.

Mistake #1 – Not registering with the admissions office either before or during your time on campus

If you don’t check in at the admissions offices, colleges have no way of knowing that you were on campus. Visiting a college and letting them know you were there can strengthen your chances of admission, because it shows you did your due diligence–commonly referred to as your demonstrated interest.

Visiting a college and letting them know you were there can strengthen your chances of admission, because it shows you did your due diligence–commonly referred to as your demonstrated interest.

The more you can connect with a college by attending an information session, taking a walking tour, emailing or interacting with admission officers on social media or attending events in your local area, it will seem to the college and the admissions officers that you’ve done your research. They can be fairly confident that you will accept and enroll if offered admission to that school. Even if you are doing a self-guided tour, make sure the admissions offices know you’re on campus.

Mistake #2 – Not researching or making pre-arrival plans prior to visiting

Whether it is knowing where to park or setting up a appointment to meet with a current student in your major, a professor or advisor or admissions counselor while on campus, it’s important to do your college visit research before you travel.

For instance: Parking can be difficult at many colleges and universities and parking tickets can be costly (based on personal experience of this author). Knowing where to park (and to not park!) will save you both time and trouble.

Although you might be able strike up a conversation with a student or two while on campus, and we do recommend that, there is a good chance that you won’t be able to spend extensive time with a student or professor unless you have planned the meet-up in advance. There are opportunities to meet students, the dean of the specific college at the university you are interested in and professors and advisors in the college, you just need to reach out and get commitments and contact information before arriving on campus.

For the more introverted student, this is an opportunity to “pretend” to be an outgoing and people-oriented person. You’ll be rewarded greatly for going outside your comfort zone. Think of it this way, you aren’t expected to know anything. If fact, high school students who don’t ask questions or present a false presentation of being all knowing are rated much lower by those you meet – and yes some of those you meet will be making notes and passing judgement to the admissions staff. There will be a file built about you.

Mistake #3 – Not having complete contact and meet-up information for your time on campus

Having each day planned out with times, meeting places, maps and all contact information will make your trip run so much smoother. Even with detailed, daily itineraries at their fingertips, we have heard that some students have forgotten to go to appointments (wow!) – not a great first impression. Imagine how much more difficult it will be to navigate an activity-filled day without a planner with this information readily accessible. [By the way, the Career Coaching for Students guidebook is a 3-ring binder that transforms into a college visit organizer.]

Here’s an example: If you’re stuck in traffic, a meeting has run long or you’re lost on campus, having contact information at your fingertips will make it easier for you to let someone know you’re still on your way.

Hotel can’t find your reservation or you arrive late at night? From personal experience, our hotel reservation had been changed inadvertently by the web-based booking agent and we didn’t know it until arriving at the hotel counter. It worked out in the end but it added a level of stress to an otherwise exciting journey. Having your confirmed booking information on your daily itinerary will make it easy for you to retrieve your reservation. We had ours.

Mistake #4 – Don’t be “that parent”

You expect your teen to be respectful and cordial when on campus, so don’t be that parent that other students and parents will talk about after the tour. Remember, this is the teen’s time to explore. It is your student who needs to ask most of the questions, to get the feel of the campus and the college community. As a parent, try your best to fade into the background while also enjoying the experience with your teen. Chances are, if they’re like most teenagers, they won’t feel at ease asking questions if you’re right beside them or overpowering them. It’s ok to ask questions but don’t be the lead, DO follow. Be helpful but not overpowering. Many deans and professors will actually ask the parents to sit in the waiting area so they can meet with the student one-on-one. We applaud this tactic. Parents, if they don’t take this proactive step, bow out and let your student meet without you.

Mistake #5 – Not taking time to explore the campus on your own

Mistake #5 – Not taking time to explore the campus on your own

Be sure to allow time to look around at all aspects of the college. Let your teen wander around on their own if they want. Visit areas you might not have seen on the campus tour. Ask the tour guide what they recommend. For example, is s/he interested in the performing arts? Find out how to visit the facilities on campus. How about the fine arts? Would it be possible for someone to show them around the studio? The library? The intramural athletics facilities? Taking the time to explore is well worth the time and effort. As subjective as it is, taking a little extra time will help your teen determine whether or not the college is a good fit for their personality and short and long term goals.

Mistake #6 – Don’t miss the opportunity for your teen to spend an overnight on campus

Some colleges offer an overnight program. Staying overnight can be an ideal second visit strategy. If this is available and something your teen would like to do, check with the admissions offices – as far in advance as possible – to find out if they offer the opportunity and if so, when these arrangements are available, their particular policies, and when to register – the spots do fill up quickly! This is one of the most valuable experiences that your student can have during the college search process; many students miss this opportunity either because they don’t know about it or because they plan too late.

If your teen does arrange an overnight, make sure you both have secondary contact information in case a problem arises; and have a talk with your son or daughter about their responsibilities when on campus. We’ve heard some stories of visiting students heading off in their own direction and not communicating with their host as to where they are. You and your teen should discuss in advance what they hope to get out of their overnight experience and understand that they are guests of the college.

Mistake 7 – Not asking relevant questions

Whether visiting as part of a group or with parents, students should be prepared with questions. Your teen should do some research before they arrive on campus so the questions they ask are those that through their research they have not found answers to – this will allow them to benefit the most from the time they have with tour guides and admissions staff. Some teens hesitate to ask questions because they are shy or afraid they may sound foolish. Others hesitate because they do not want to annoy the others in the group by holding up the tour. Neither fear is warranted.

Neither fear is warranted.

In fact there’s no better time to ask questions than during a campus visit. If your teen has questions in mind, they should ask them. Refer to our other article, College Tours: Questions to Ask on a College Visit – And Who to Ask for a starter list of great questions. It will help them make informed decisions.

When it comes to asking questions, the student conducting the tour is a great warm up opportunity. Also ask admissions staff, teaching and laboratory staff and even current students you meet throughout the day.

Mistake #8 – Getting impressed by the bells and whistles

Campus visits are a great opportunity for colleges to sell their services to eager students and parents. While most colleges and universities do deliver on their promises, they tend to highlight their best side while downplaying some of their shortcomings. The landscaping along the driveway will probably be immaculate and you are likely to hear about the number of volumes in the library, the new sporting or theater facility or hi-tech classrooms. Don’t be immediately swayed. Look around and ask questions.

During your campus visit, it is important to stay focused on what matters most to your teen. But you can also pay attention to the things that will make a difference to you as a parent. For instance, if you know your son or daughter is interested in studying in the STEM fields, check out the labs and the research facilities – don’t get caught up in the hype about the rock wall.

Mistake #9 – Not making the effort to gather ‘insider’ information

To find out how things really work, spend some time getting insider information from those who have nothing to gain — current students. Sitting down and having coffee or lunch with a current student will provide valuable insight into the things that really matter to your student. Before the day of your campus visit, find students through Facebook or other social media that attend and make a list of questions to ask students. You’ll find juniors, seniors and recent graduates are likely also on LinkedIn.

Questions your student might ask are:

- “What do you like most about the college?”

- “Why did you choose this college?”

- “What’s it like to live in this college dorm?”

- “What does your typical weekend look like?”

- “Might you tell me what don’t you like about the college?”

- “Do you find the professors, administrators and staff helpful/supportive?”

- “Can I text you if I have additional questions?” (ask for their phone number)

Mistake #10 – Discounting the importance of the surrounding area

Ignoring the surrounding area is a mistake that could impact your teen’s whole college experience. Each community surrounding a college is completely unique. Let’s say you live in a rural area and your teen is visiting a college in a big city with very little campus area or the campus is spread out in a patch work manner. If you have time, hop on a bus or subway that may be the primary transportation that your teen will use often. Find out where the dorms will be – will it be too noisy? Are they within walking or biking distance to most classes.

If your teen comes from a bigger city with a lot going on, how will it feel to be in a more suburban or rural campus? How easy is it to get to the grocery store or Target? Does the school provide transportation or do they contract with the public transportation system of the city?

Surroundings do matter. Your teen will be spending four to five (?) years in college and it is important to not be in the wrong setting. Spend some time discovering the restaurants, cultural centers, museums and other facilities that the neighborhood offers and ask your teen if this is a place where they would be happy to call home.

A campus visit can give you and your teen great information. Information that will help them make the right college choice.

College Visit Checklist by Career Coaching for Students

College Board campus-visit-checklist

Career Coaching for Students College Visit PROs and CONs Worksheet

Tap here for other articles that may be of interest on our blog.

Preliminary Study Shows Critical Skill Missing in College Freshman – but why?

Is Decision Making as a Skill One of the Keys to Student Success?

5 Reasons Parents Should Invest In Career Coaching for High School Students

Copyright © 2018 Success Discoveries, LLC

Career Coaching for Students™ is a trademark of Success Discoveries, LLC

Sign our guestbook and get free stuff.

Have a question for Carl Nielson, author of this article and creator of the national program Career Coaching for Students?

To make the most of your visits, you should prepare thoughtful questions to ask on each college visit. The college tour is just one part of your college visit. Set your goal to meet with more than just the college tour guide and watch the promotional film or PowerPoint slideshow. This guide will provide you with a comprehensive college visit checklist of questions for your tour guide, current students, admissions officers, financial aid officers and professors. Plus, we’ll offer some advice on what not to ask.

To make the most of your visits, you should prepare thoughtful questions to ask on each college visit. The college tour is just one part of your college visit. Set your goal to meet with more than just the college tour guide and watch the promotional film or PowerPoint slideshow. This guide will provide you with a comprehensive college visit checklist of questions for your tour guide, current students, admissions officers, financial aid officers and professors. Plus, we’ll offer some advice on what not to ask. Besides sampling the dining food or hanging out on the quad, you can also learn about the student experience from your tour guide who is usually a current student, and other current students that you meet (summer tours present less opportunity to see the campus the way it will be during the busy Fall and Spring semesters).

Besides sampling the dining food or hanging out on the quad, you can also learn about the student experience from your tour guide who is usually a current student, and other current students that you meet (summer tours present less opportunity to see the campus the way it will be during the busy Fall and Spring semesters).

Is it easy to change your major? Can I enter as a freshman with a double major?

Is it easy to change your major? Can I enter as a freshman with a double major?

Making contact with the admissions office can not only get your questions answered, it can also get your “demonstrated interest” on file, which may help when it comes time to reviewing your application. Rather than appearing as an anonymous applicant, admissions officers may recognize you from a meeting, email, or other records of contact. Not all schools keep track of this, but for many, your visits are noted in a file and demonstrating interest by the number of visits may help show your enthusiasm for the school and thereby give you a an edge over applications that don’t show any visits.

Making contact with the admissions office can not only get your questions answered, it can also get your “demonstrated interest” on file, which may help when it comes time to reviewing your application. Rather than appearing as an anonymous applicant, admissions officers may recognize you from a meeting, email, or other records of contact. Not all schools keep track of this, but for many, your visits are noted in a file and demonstrating interest by the number of visits may help show your enthusiasm for the school and thereby give you a an edge over applications that don’t show any visits.

Your first step is scheduling and signing up online for your college tours, as well as any other meetings or overnight stays. The best time to tour is when classes are in session so you can get the truest sense of the college in action.

Your first step is scheduling and signing up online for your college tours, as well as any other meetings or overnight stays. The best time to tour is when classes are in session so you can get the truest sense of the college in action.

by

by

Most high-achieving students are not provided much attention unless they specifically request assistance. Most students believe they are suppose to somehow magically know what they want to be or have the confidence and ability to figure it out – yet over 90% of students do not have clarity nor the confidence to adequately make decisions effectively.

Most high-achieving students are not provided much attention unless they specifically request assistance. Most students believe they are suppose to somehow magically know what they want to be or have the confidence and ability to figure it out – yet over 90% of students do not have clarity nor the confidence to adequately make decisions effectively.

There are 5.3 million Americans who suffer from Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s is a debilitating brain disease that robs people of their memories, the ability to speak, read, swallow and enjoy life.

There are 5.3 million Americans who suffer from Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s is a debilitating brain disease that robs people of their memories, the ability to speak, read, swallow and enjoy life. Something that is equally devastating to watching your loved one succumb to this disease is to think that someone who could cure this disease will not because they have not had the opportunity to identify, understand and pursue career paths that match their interests and talents.

Something that is equally devastating to watching your loved one succumb to this disease is to think that someone who could cure this disease will not because they have not had the opportunity to identify, understand and pursue career paths that match their interests and talents.

Entering college is without question one of the most exciting and fun times for young adults and their parents. Many tasks have been completed to get to this point. Often, however, declaring a major is not one of them.

Entering college is without question one of the most exciting and fun times for young adults and their parents. Many tasks have been completed to get to this point. Often, however, declaring a major is not one of them.